By Jacquie Rahm, CCLS, CTRS-C, YMHFA

Behavioral health challenges, including suicidality, are preventable and treatable. Despite this, a global stigma related to behavioral health reduces help-seeking and increases feelings of shame and guilt. This is concerning, as behavioral health challenges are a leading cause of death for all ages, with expressions of suicidality starting to increase around age 10-years (WHO, 2019). One of the most effective prevention strategies any professional can take is a stand against stigma.

The Power of Language

One of the simplest way to address stigma is to model sensitive and inclusive language for others. Our language has the power to directly and indirectly affect our perceptions of an individual, situation, or circumstance. Problematic language reinforces problematic stereotypes, influencing acceptance of diagnosis, care, and self-worth. When it comes to behavioral health and suicidality, language is more than social sensitivity and correctness. It’s about saving lives.

As child life professionals, we know the positive influence sensitive and inclusive language can have on coping, understanding, perception, and acceptance. Have you ever modeled or gently nudged a medical team member into saying, “small needle poke” instead of “big stick?” The same can be done with language about behavioral health and suicidality.

When speaking about behavioral health, it is important to be positive, sensitive, and put the person first. Try to avoid harsh words like, “suffering,” or derogatory labels like, “crazy,” as they perpetuate stigmas and invalidate the needs of the individual.

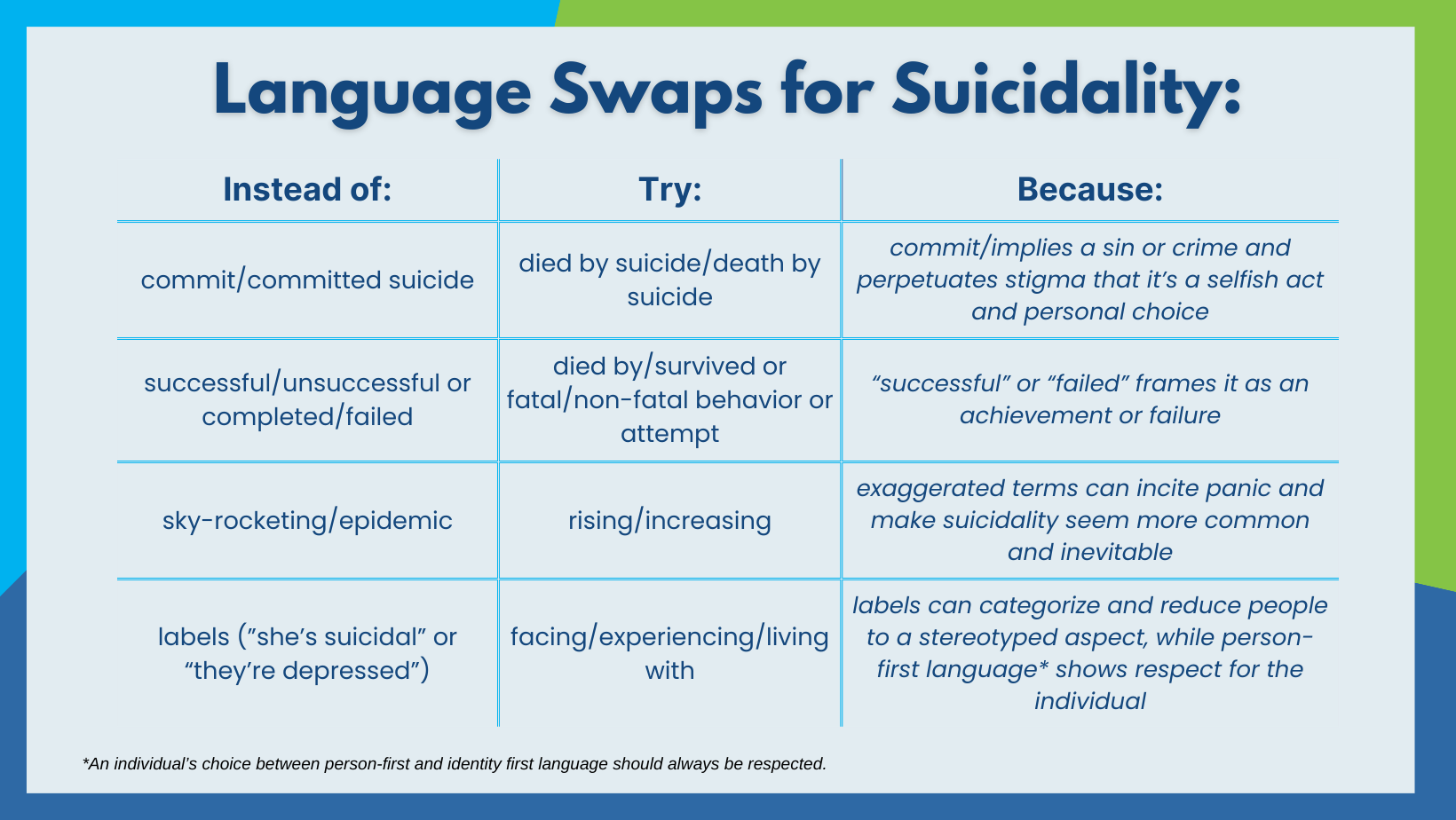

Here are some simple language swaps related to behavioral health and suicidality that you can incorporate into your everyday practice:

Personal tip: If you catch yourself using problematic language, correct yourself out loud to turn it into a positive learning experience for those around you.

Beyond Modeling

Modeling inclusive language may not be enough at times. The 5Ds of Bystander Intervention (Right to Be) was developed as a way to equip individuals with skills to help them actively intervene when witnessing biased acts or comments.

Direct action: Call out the inappropriate behavior and tell the person to stop (may escalate the situation – use with caution and discretion).

Distract: Interrupt the situation (e.g., ask an unrelated question, start a conversation with one or both parties, create an excuse to remove one or both parties, etc.).

Delegate: Ask someone else to help intervene, either with you or on their own (e.g. staff witnessing the situation, unit management, a supervisor, etc.).

Document: Write notes or take videos of the situation to accurately record details.

Delay: When unable to act in the moment (for many reasons including safety, comfort, or time), check in after-the-fact to address the situation and offer support when able.

Awareness of our language is helpful with being more inclusive and sensitive. Knowledge about the 5Ds is helpful when making the intentional choice to intervene. But how do we put it into practice?

Here are some examples of how the 5Ds can be used in situations you may encounter in the medical setting:

EX1: In rounds, it is said that this is the child’s third failed suicide attempt, and that mom, “is also a little crazy, so… I do feel sorry for the kid! Can you imagine living like that?”

Direct action: “What do you mean by that?” “Do you mean mom has a diagnosed mental health disorder? Do we know which one? That may be helpful for the psych team.” Explain that people usually attempt suicide multiple times, and describing it as “failed” may further trigger feelings of low self-worth. Explain that everyone’s social situations are different, and it is not helpful for the medical team to judge the family’s situation (e.g., parent work schedule, child hobbies, cultural influences, diagnosed disorders, etc.)

Distract: Ask a medically relevant question (e.g., “Are they able to get out of bed yet? I was thinking a walk outside might be a good change of scenery.”)

Delegate: Ask another team member who is also trying to advocate for the family to help you in addressing the situation. For example, “hey, I think it’s really important the we help the team understand the family’s situation a little more sensitively. Would you please tell [staff] what the mother shared with you about her struggles and treatment?”

Delay: Speak with the staff member later and explain, “I know it wasn’t your intention, but the description of the family’s situation came off a little insensitive to me.” Explain that terms like “failed” and “crazy” can reinforce negative self-worth and stigmatization.

EX2: Your favorite resident jokes, “[while smiling with so much resident confidence] I mean, what a stupid way to try to kill yourself! If they really wanted to die, they should have done [xyz other method]. HAHAHA.”

Direct action: Strategically ignore (do not laugh or smile). If others start laughing, make it clear you do not find it funny.

Distract: Ask a medically relevant question to get back on track, before anyone has time to respond to the joke.

Delegate: Suggest to the attending physician that talking/joking about patient and family stress might not be the most appropriate when in areas that people could walk by. Or, just straight up inform the attending that an inappropriate comment was made.

Delay: Ask to talk later, “I know you were just trying to be funny, but some people really do think like that! And making the choice to die isn’t a joke. What if someone listening had mental health struggles, or the child or family walked by? That comment could have been really triggering for them.”

EX3: You walk into a patient’s room who is here post-suicide attempt. A family member says, “It’s all for attention. They had their phone taken away and now they’re acting out. If they think that is going to change my mind, they have another thing coming.”

Direct action: “We want everyone to feel safe here and know that we recognize how difficult and complex depression really is.”

Distract: Explain all of the amenities available on the unit for the child and the family, encouraging family to take breaks. If possible, remove one party from the situation (example: offering to engage in an activity alone with the child (and sitter) to speak more freely and validate child feelings).

Delegate: Tell the psychiatrist about the comment before the psych team rounds today so they can provide education and support to the child and family.

Document: Document quotes from the family in child life chart note with a recommendation for other staff on how to address similar comments if they also experience this in front of the child.

Delay: Later, privately explain to the family that you recognize how unexpected this hospitalization is for them, and that the team will try to support them as best as possible. “But, we want your child to feel comfortable and safe in this hospital. Regardless of motivation, this is very serious and we want to make sure they get the help they need and they feel supported.” You can also explain how language like that is potentially harmful to other children and families admitted for similar reasons, and it will not be tolerated in areas where others could overhear.

More information on the 5Ds:

- The Right To Be website has information on the 5Ds and other training they offer. https://righttobe.org/guides/bystander-intervention-training/

- Here is a YouTube playlist with short videos on each of the 5Ds geared towards children so that they feel empowered to act on behalf of themselves and their friends. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL3wdAcMaXQVqFKg4lKvN3NqTBqz4tsscM

American Psychological Association (2021). Inclusive language guidelines. https://www.apa.org/about/apa/equitydiversity-inclusion/language-guidelines.pdf

Aunt Martha’s Health and Wellness (2023, May 16). Talking about mental health: Using inclusive language to make every word count. https://www.auntmarthas.org/news/talking-about-mental-health/

Bulthuis, E. (n.d.). 7 terms to avoid when talking about mental illness, and better ones to use. Health Partners. https://www.healthpartners.com/blog/mental-illnesses-terms-to-use-terms-to-avoid/

CAMH (n.d.). Words matter: Learning how to talk about suicide in a hopeful, respectful way has the power to save lives. https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/words-matter-suicide-language-guide.pdf

Right to Be (n.d.). The 5ds of bystander intervention. https://righttobe.org/guides/bystander-intervention-training/

World Health Organization (2019). Suicide worldwide in 2019: Global health estimates. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643