Innovative Collaboration Comes Alive with Shared Vision

ACLP Bulletin | Summer 2021 | VOL. 39 NO.3

Julie Piazza, MS, CCLS, Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, MI

Andrea Reynolds, BS, Ann Arbor Hands-On Museum, Ann Arbor, MI

Jayne Griffin, Ed.D, Creative Discovery Museum, Chattanooga, TN

Suzanne Ness, Creative Discovery Museum, Chattanooga, TN

Rachel Hamilton, Thinkery, Austin, TX

Development of the Program

The initial inspiration for this program occurred through many years of community-based “one-off” medical play programs facilitated during Child Life Month as recognition of the role of child life specialists as part of ACLP’s founding organization Association for the Care of Children’s Health (ACCH) and Child Life Council (CLC). Pediatric nurses also facilitated hands-on activities during Nurses’ Week in many local communities. The chief executive officer of C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital recalled some of these programs at the Ann Arbor Hands-On Museum (AAHOM) and suggested to the child life director and patient experience project manager that, since the new hospital was now complete, it would be a wonderful time with more space to explore expanding community outreach and partnerships.

The initial meeting in December 2012 included the AAHOM director, museum outreach manager, child life director, and patient experience project manager (also a seasoned child life specialist). There was a rapid-fire brainstorming exchange of exciting ideas to try implementing, as well as suggestions of potential grants from community foundations and donors who supported both institutions. The collaborative communication has continued over the years with initial seed grants from the hospital followed by local, regional, and national grant applications, initiated by the museum with hospital partners named in each and every grant. The child life specialist/project manager has remained an integral part of the oversight of the program and has continued to explore ways to further public health and community engagement with outreach, distance learning, and avenues to involve multidisciplinary health care professionals highlighting information sharing, collaboration, and education as pivotal patient- and family-centered care pillars.

Word spread, and the program has expanded to additional museum and hospital partners and increased grant opportunities. Interest on the museum/science center side was generated after presentations at national museum conferences and the development of a Community of Practice as part of the Association for Science & Technology (ASTC). This work was also presented at the 2018 ACLP conference in Washington, DC, and received wide-spread interest as a community-building opportunity.

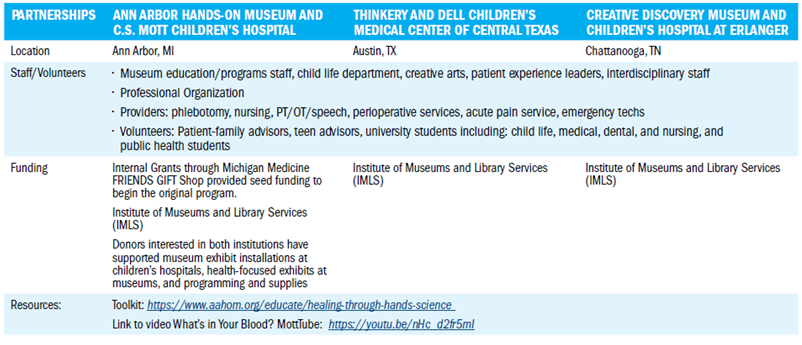

Several of our museum/hospital partners have also worked with child life specialists in their respective institutions to leverage health science discovery as education and distraction opportunities in permanent or rotating museum exhibits in hospital or clinic waiting spaces. In addition to C.S. Mott and AAHOM, other lead hospital/museum partners named in the national grant are: Erlanger Children’s Hospital and Creative Discovery Museum in Chattanooga, TN, and Dell Children’s Hospital and Thinkery in Austin, TX.

The Program in Action

Programs in the hospital setting take many forms, using various tools and resources. Many programs call for museum staff to bring science-focused, tabletop activities into a designated space within the hospital. Possible locations include a family waiting room, an outpatient clinic, a communal setting for in-hospital patients, or even infusion centers and bedsides, when requested. Successful hospital activities are open-ended and appropriate for a variety of ages, allowing children to actively participate at any level of involvement. Activities will often include easy to find materials to encourage further exploration later. Though some are health-focused, many are not, since distraction from health issues is a primary goal. For example, tabletop catapults can be engaging and exciting for kids as they add a payload (puffballs, ping pong balls, etc.) and try to hit a target. Children can engage in the engineering process and experiment with altering different variables. Children of all ages can be successful, the catapult demonstrates scientific principles, and the activity is portable, even to a bedside. Museum educators can also connect the principles learned from this activity back to an exhibit at their location or to a patient’s memory of a past museum visit, if applicable. Most importantly, this activity provides distraction, play experiences, and normalcy for the population being served.

HTHOS Community Outreach School Event Partners

HTHOS Community Outreach School Event Partners

When patients are unable to visit programming spaces during planned museum visits, pre-made museum activity backpacks can be distributed. Backpacks can include games and activities that would occupy children for a longer period of time than educator-led activities and contain facilitation instructions for caregivers. Advisors from the hospitals’ Patient Family Advisory Councils provided many ideas and helpful feedback on the kinds of activities needed and the benefits of the backpack being deliverable to patients and families, especially during hospitalizations and/or lengthy outpatient clinic appointments. The backpacks continued to be helpful resources during pandemic restrictions and have been used as part of the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital virtual summer camp.

Digital programs are another way HTHOS has reached children in the hospital. Closed-circuit TV broadcasts can be presented in different formats, but the science demo has been most effective.

Typically, two to three different science demonstrations are presented, and sometimes an activity can have a “do-along” component using items that are available in the hospital room, like straws from a meal tray or washcloths and water. With help from the hospital’s child life department staff, small activity kits can also be distributed to interested patients who want to join in with the video presentation. Many science museums are already equipped to deliver virtual programming in this fashion and can easily adapt to delivering for a hospital audience. This type of programming also works to reinforce connections to the community outside of the hospital walls.

Even for those who are not currently experiencing a health care crisis, it is likely that at some point they will become a patient or know someone who has a serious medical event. Partnerships like HTHOS can provide preparation and positive coping skills to those who are not yet patients, with a goal of providing positive experiences early in life that influence health outcomes later. Gathering community resources in one setting, such as a museum, can build trust in health care providers and demonstrate the benefits of patient-centered care. These museum events included many different areas of health care, such as nursing, nutrition, orthopedics, perioperative services, phlebotomy, physical therapy, mental health services, and pharmacy, to emphasize the multiple dimensions and necessary collaboration that make up quality medical care.

At one HTHOS community-based event, a second-grade girl in a leg cast and crutches hovered over the Teddy Bear Clinic surgical table. With her play scalpel and forceps, she intensely focused on her play operation. The father stated he had never seen anything like this event before and wished he had experienced something similar in his youth, as he feared the hospital. Once the facilitator learned his daughter wanted to become a “brain doctor,” she introduced her to a volunteer medical student. Her eyes stayed transfixed on “a real medical student” as she asked question after question. This event took place in a high-poverty, minority, and immigrant community. The event was a unique experience for all youth, especially marginalized youth. Children learned about medical procedures and coping strategies and were able to envision themselves in roles of medicine, science, and child life.

Children and Dell Children’s Hospital medical professionals model an MRI procedure. Photo: Michael Malloy

Children and Dell Children’s Hospital medical professionals model an MRI procedure. Photo: Michael Malloy

C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital OR Nurse interacting with the Children at HTHOS Community Event. Photo: Ari Morris

C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital OR Nurse interacting with the Children at HTHOS Community Event. Photo: Ari Morris

The Value of Partnership Collaborations

Shared goals are important for healthy thriving partnerships. Research shows that hospitalized children report increased levels of anxiety (Potaz et al., 2012), as do the caregivers of these patients (Ellerton, 1994). Children communicate and process emotions through play. This provides an outlet for anxiety and fear, which ultimately gives children a sense of control (Koukourikos et al., 2015). Children’s museums and science centers have developed play-based, exploratory activities that engage children and provide distraction. Staff in these organizations are typically very adept at engaging a variety of children in a variety of settings. In the health care setting, child life specialists and other providers are constantly pivoting to build rapport with children and families quickly to support medical experiences, and have greatly appreciated the opportunity to be in the community sharing those important public health messages. One health care partner has framed this as “an opportunity to improve patient experiences before they occur.”

Teddy bear clinics at museums present an educational opportunity for multiple participants. The experience places children in the role of the medical professional, and they are afforded the opportunity to learn about medical equipment as well as process their own medical experiences. The teddy bear clinics have also provided a learning experience for child life interns at C.S Mott. During their internships and fellowships, students are immersed in learning opportunities related to diagnosis education, procedure support, and developmental play with patients within the hospital setting. This outreach opportunity offers opportunities to practice their medical play facilitation skills in a non-traditional setting to expand their child life reach into the community.

C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital OR Nurse interacting with the Children at HTHOS Community Event. Photo: Ari Morris

C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital OR Nurse interacting with the Children at HTHOS Community Event. Photo: Ari Morris

Conclusion

Successful partnerships between museums and hospitals result when one partner becomes the missing piece of the other partner’s puzzle. Children’s museums are no longer confined within the walls of a building, but look to reach outside of themselves to make connections in their community. This task requires community partners to bring expertise and authenticity into the museum setting. Hospitals provide real staff, objects, and experiences found in the medical profession. These museum puzzle pieces are filled by hospitals. Hospital and child life staff look to provide normalcy and connection to patients during their stay. Local museums can provide opportunities for science discovery and community connection.

The children referenced in this article had excellent medical interventions and care, and museum educators, in collaboration with child life, were able to offer discovery, distraction, and normalcy as a part of their hospital experience. Additionally, public health opportunities have been expanded to support coping and offer natural teachable moments in community settings. In these moments of normalcy, the child’s potential for physical, intellectual, and emotional healing has been revealed. HTHOS provides a nexus where the life-giving properties of medicine and education meet to positively affect the trajectory of children and their caregivers. This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services [MA-20-16-0114-16]. The views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

With acknowledgement to: Jennifer Gretzema, MA, LPC, CCLS, Child & Family Life Department, C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, Michigan Medicine in Ann Arbor, MI, and Catherine Mwai, BS, Health and Wellness Teacher, Todd County Elementary School, Rosebud Reservation, Mission, SD and Former Community Partners Intern, Office of Patient Experience, Michigan Medicine in Ann Arbor, MI.

The Child Life Perspective

A seasoned child life specialist from C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital (Mott) recalls an impactful experience from a family encounter during a museum-based HTHOS event. “An eight-year-old child was participating in our teddy bear clinic at the Hands-On Museum. During play, he shared that his sibling was a current patient at Mott. As the child placed an IV and bandages on his teddy bear, his grandma shared how timely this intervention was for their family. Grandma relayed that her grandson’s older sibling had just been diagnosed with cancer that weekend. Using the natural language of play, this child was able to work through this new medical development in his family and claim control and mastery over this event personally.”

The Museum Educator Perspective

From the museum educator perspective: “A six-year-old child had been critically injured in a school bus accident. His right side was paralyzed and he had not spoken or shown emotion since the accident three weeks before. His dad learned from a child life specialist that children’s museum staff were onsite facilitating bedside activities with other hospitalized children and requested that museum educators come to his child’s room to try to engage his son, who had not been out of his bed since the accident. The museum educator held an undecorated gingerbread house out to the child demonstrating how candy could be dipped into icing and placed on the house. Then she offered the child an opportunity to respond. Gently, lifting his hand from under the sheets, he began putting candies onto the house. Hospital staff who were in the room were amazed at the child’s response and asked other staff to, “Come see.” Then, the engagement expanded even more. The child took a candy, dipped it into the icing as if he was going to place it onto the house, but instead, he put it on his head and gave a half

smile to the museum educator. The implications of the child’s response showed the child’s spirit emerging underneath his traumatized and paralyzed exterior.

Though the activity brought to the side of this child’s hospital bed was not a miracle cure, it offered a new distraction and discovery opportunity for that child to play, explore, and engage in normalcy for a brief time. In that moment of normalcy, hospital staff, the father of this child, and museum partners were able to witness hope in action. The museum educators learned the impact of collaboration with nearby community resources. The family was able to share in future community connections when they visited he museum after being discharged from the hospital.

|

Table 1.

Research Evidence/Effort Categorized by Component of Child Life

REFERENCES

Ellerton, ML., & Merriam, C. (1994). Preparing children and families psychologically for day surgery: An evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19(6), 1057-62.

Koukourikos, K., Tzeha, L., Pantelidou,P ., & Tsaloglidou, A. (2015). The importance of play during hospitalization. Mater Sociomed, 27(6), 438–441.

Li, H.C.W., and Lopez, V. (2008). Effectiveness and appropriateness of therapeutic play intervention in preparing children for surgery: A randomized controlled trial study. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 13, 63-73.

Michigan Medicine. (2020). Office of Patient Experience.

https://medicine. umich.edu/dept/office-patient experience Child & Family Life.

https:// www.mottchildren.org/mott-support-services/cfl

Potaz, C., Vilela De Varela, M.J., Coin De Carvalho, L., Fernandes Do Prado, L., & Fernandes Do Prado, G. (2012). Effect of play activities on hospitalized children’s stress: A randomized clinical trial. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Early Online, 1–9.

Rollins, J., Bolig, R., & Mahan, C. (2005). Meeting children’s psychosocial needs across the health care continuum. Preparing Children, and Play in Healthcare Settings, pp. 43-117.